The American legal profession is grounded in principles of excellence, rigor, and achievement. From law school admissions to courtroom triumphs, attorneys are rewarded and celebrated for measurable accomplishments. Yet, beneath the façade of professional success, a silent crisis is unfolding. An alarming number of attorneys report symptoms of anxiety, depression, burnout, and existential despair. These mental health challenges are not simply byproducts of long hours or adversarial dynamics—they are often rooted in a deeply ingrained psychological dependence on external validation as a proxy for self-worth.

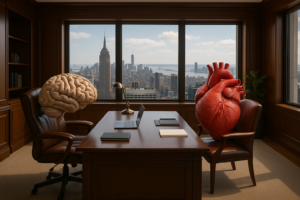

This article explores the formative developmental conditions that give rise to this psychological structure, its functional benefits and eventual limitations, and the therapeutic implications for working with attorneys who reach a professional peak only to discover an inner emotional void. Drawing from psychological theory, clinical insight, and spiritual traditions, this discussion aims to shed light on the unseen architecture of the attorney’s psyche—and how its deconstruction may be essential for long-term well-being.

Childhood Roots: Emotional Neglect and the Allure of Achievement

A. The Emotional Ecosystem of High-Functioning Families

Many attorneys emerge from family systems that are outwardly successful yet inwardly constrained when it comes to emotional expression. These are often families that are achievement-oriented, emotionally avoidant, and governed by implicit rules around performance, composure, and intellectual competence. Vulnerability—especially the kind involving fear, sadness, or dependency—is frequently regarded as a weakness to be corrected rather than an essential dimension of human experience to be nurtured.

B. The Emergence of External Achievement as a Survival Strategy

In the absence of attuned emotional mirroring, children in these families often begin to discover that achievement is a reliable currency for attention, approval, and love. Gold stars, high test scores, and class accolades begin to take the place of emotional intimacy. The child becomes proficient in attuning not to their internal state, but to the evaluative gaze of parents, teachers, and later, institutions. Over time, achievement morphs from a healthy expression of potential into a necessary means of survival—a psychologically adaptive, but ultimately constricting, strategy.

The Reinforcement Loop of Legal Education and Practice

A. Law School: Perfectionism Codified

Legal education in the United States often amplifies this early developmental adaptation. The culture of legal academia prizes intellectual mastery, competitiveness, and external ranking. It rewards meticulous analysis but leaves little room for self-reflection or emotional integration. The Socratic method, class rankings, and elite clerkships continue the message that your value is what you produce, how well you perform, and who says you’re better than your peers.

B. Practice: Outcome-Driven Metrics of Worth

Upon entering practice, attorneys enter a profession where identity is merged with performance. Billable hours, win/loss records, client satisfaction, partnership status—all become metrics that signal worthiness in a system that validates people only through measurable output. This can be particularly intoxicating—and dangerous—for those whose early sense of self-worth was already externally tethered.

The Crisis of Arrival: Success and the Collapse of Meaning

A. The Emptiness Behind the Credentials

For many attorneys, the external validation strategy works—until it doesn’t. After climbing the ladder to professional recognition, many are left with a troubling realization: achievement does not translate into sustained fulfillment. The momentary euphoria of success is soon followed by a return of the very emptiness it sought to stave off. This existential disillusionment often precipitates a deeper psychological crisis that can manifest in anxiety, depressive symptoms, substance use, or relational breakdowns.

B. The Limits of Cognitive Mastery

Because most attorneys have been rewarded for their cognitive prowess, their first impulse is often to try to “think” their way out of the problem. But this particular crisis cannot be solved through analysis or intellect. Indeed, what is needed is not more doing, but a radical reorientation toward being—a foreign and often frightening proposition for those who have never been shown how to access this domain of the self.

Toward Recovery: Cultivating Inherent Worth and Spiritual Grounding

A. The Necessity of Spiritual Development

Recovery from validation-dependence requires more than behavioral change. It necessitates a spiritual turn—not in a religious sense, but in a psychological sense that involves connecting with something deeper than achievement, status, or intellect. This involves a recognition of inherent worth, which is not contingent on performance, approval, or outcome. In clinical terms, this is the development of a stable, cohesive sense of self rooted in being rather than doing.

B. Paradox and the Letting Go of Striving

Here lies the paradox: the very tools that enabled the attorney to succeed—goal-directed behavior, strategic thinking, perfectionism—must now be set aside. In their place, attorneys must learn to tolerate ambiguity, cultivate silence, and reconnect with vulnerable aspects of the self that were long exiled. Therapeutically, this process often begins with deconstructing the myth of meritocracy as identity, and creating space for practices such as mindfulness, meditation, and compassionate self-inquiry.

C. The Role of the Clinician

Clinicians working with attorneys must tread carefully. The lawyer’s default orientation toward control, certainty, and analysis can resist the spiritual dimensions of therapeutic work. Effective treatment must meet attorneys with intellectual rigor while inviting them toward experiential processes that are deeply unfamiliar. The goal is not to undermine achievement, but to expand the terrain of identity such that self-worth is not exhausted by external metrics.

Conclusion

The attorney’s overreliance on external validation is not simply a character flaw—it is a rational adaptation to emotionally impoverished environments and a profession that prizes performance over presence. Yet, if left unexamined, this adaptation can calcify into existential despair. The task for the legal profession—and for those who support it—is to recognize that success without self-connection is hollow, and that sustainable well-being lies not in more achievement, but in a deeper relationship to self that does not require an audience.

The journey from validation to wholeness is not linear, and it defies the logical schemas so beloved by lawyers. But it is a journey that must be undertaken if the legal profession is to cultivate not only excellent attorneys, but whole human beings.