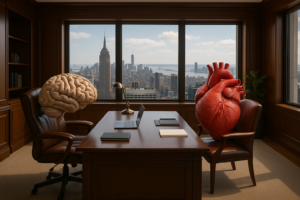

While much scholarly attention has been devoted to the psychological toll of legal education and law practice, less consideration has been given to the ways in which these experiences can serve as crucibles for the development of emotional strength and adaptability. This article contends that legal training and the practice of law, though often high-pressure and adversarial, can function as potent developmental environments that foster psychological resilience. Drawing on empirical research in developmental psychology and resilience theory, this article maps the attributes of legal education and professional legal work onto established precursors of psychological resilience. It proposes a reframing of legal training as not only intellectually rigorous but emotionally formative, offering opportunities to cultivate key intrapersonal skills such as distress tolerance, cognitive flexibility, and purpose-driven motivation.

Introduction

The legal profession has long been the subject of psychological critique. Studies have consistently shown that law students and practicing attorneys experience elevated levels of anxiety, depression, and burnout compared to the general population.1 While these concerns warrant serious attention, the prevailing focus on pathology risks overshadowing the psychological strengths that legal education and law practice can cultivate. If viewed through a developmental lens, the rigors of legal training and practice may also serve to enhance emotional strength, cognitive adaptability, and long-term psychological resilience.

This article explores how the structural demands and cultural expectations of the legal profession can, in many cases, promote qualities associated with resilience—particularly when attorneys engage these experiences with awareness and support. By drawing parallels between known resilience-promoting life experiences and the conditions of legal training, we seek to identify ways in which legal culture may, paradoxically, strengthen the very psychological capacities it is often accused of eroding.

Understanding Resilience: Psychological Foundations and Empirical Evidence

Resilience is broadly defined as the ability to maintain or regain psychological well-being in the face of adversity. Contemporary psychological research has identified a constellation of personal and environmental factors that contribute to resilience. These include:

(1) Exposure to manageable stress (“stress inoculation”);

(2) A strong sense of agency and control;

(3) Social support and mentorship;

(4) Cognitive flexibility and reappraisal capacity;

(5) A sense of meaning or purpose in adversity.

In a landmark longitudinal study, Emmy Werner followed nearly 700 children from birth to adulthood in Kauai, Hawaii, and found that one-third of the at-risk cohort grew into competent, confident, and caring adults despite exposure to severe adversity.2 Key protective factors included problem-solving skills, a sense of autonomy, and supportive adults outside the family system.

More recently, George Bonanno’s research on “resilient trajectories” after traumatic events revealed that most individuals are far more resilient than previously believed, particularly when they can access supportive structures and make meaning of their experience.3

The U.S. Army’s “Comprehensive Soldier Fitness” program, designed to promote resilience in high-stress environments, emphasizes many of the same factors—especially cognitive flexibility and psychological strength developed under pressure.4

Legal Training as a Context for Resilience-Building

Legal education, particularly in elite institutions, immerses students in a culture of high expectations, public performance, and sustained intellectual rigor. While these experiences can be sources of stress, they also echo the “controlled adversity” that resilience research identifies as a key developmental crucible.

(A) Stress Inoculation Through High-Stakes Learning

Cognitive-behavioral research into “stress inoculation training” (SIT) has shown that gradual exposure to manageable stressors—combined with opportunities for reflection and skill-building—can foster durable coping mechanisms.5 The Socratic method, mock trial competitions, and real-time issue-spotting under time constraints all approximate this model. Students learn to navigate high-stakes environments, not by avoiding stress, but by developing internal regulatory strategies for managing it.

(B) Fostering a Sense of Agency in Uncertain Terrain

The ambiguity inherent in legal reasoning—where outcomes are rarely black-and-white—requires students and practitioners to develop a tolerance for uncertainty and a willingness to make decisions without perfect information. This experience can enhance what psychologists refer to as “internal locus of control,” a key marker of resilience.6 The ability to take ownership of outcomes in uncertain or complex environments strengthens one’s adaptive capacity over time.

The Practice of Law and the Consolidation of Emotional Strength

The daily work of legal professionals—negotiating conflict, managing client crises, navigating institutional politics—places continuous demands on emotional regulation. However, when approached with self-awareness and structured support, these very challenges can deepen practitioners’ emotional maturity and adaptability.

(A) Cognitive Reappraisal in Advocacy and Strategy

A central skill in legal practice is the ability to reframe facts and narratives. Lawyers routinely adopt multiple perspectives to anticipate counterarguments and craft persuasive strategies. This mirrors the cognitive strategy of “reappraisal,” known in resilience literature to be one of the most effective techniques for emotional regulation.7 The lawyer’s mental flexibility—if applied not only externally but internally—can become a tool for managing difficult emotions and experiences.

(B) Emotional Endurance in Client-Centered Representation

Attorneys are often called upon to remain composed during emotionally charged scenarios, such as delivering bad news, de-escalating conflict, or holding space for client distress. These repeated encounters with human vulnerability, when navigated with integrity and reflection, may cultivate greater emotional bandwidth and compassion resilience—akin to that developed in therapeutic or caregiving professions.8

Reframing Legal Culture: Supporting Growth Over Defense

While the legal profession’s cultural emphasis on perfectionism and adversarial dominance can obstruct emotional development, a parallel cultural shift is underway. Programs focusing on lawyer well-being—such as those promoted by the American Bar Association’s Well-Being Pledge and the movement toward trauma-informed legal practice—are beginning to foreground emotional resilience as a professional asset rather than a private liability.

To foster resilience more intentionally, legal institutions can:

(1) Integrate reflective practices into legal education (e.g., guided journaling, mindfulness workshops);

(2) Encourage peer mentorship models, replicating the social buffering effects observed in resilience studies;

(3) Frame difficult experiences as growth opportunities, rather than as failures of competence.

Conclusion

The story of law and psychology is too often told in terms of tension and damage. This article has attempted to balance that narrative by showing how legal training and practice—while undeniably stressful—can also forge deep wells of emotional strength and adaptability. When viewed through the lens of resilience research, the experiences of attorneys are revealed not only as threats to well-being, but also as potential engines of psychological growth. Legal culture must continue to evolve to support these outcomes, but the raw material for resilience is already embedded within the fabric of legal life.

References

(1) Krill, Patrick R., Johnson, Ryan, and Albert, Linda. “The Prevalence of Substance Use and Other Mental Health Concerns Among American Attorneys,” Journal of Addiction Medicine, 10(1):46–52 (2016);

(2) Werner, Emmy E. Overcoming the Odds: High Risk Children from Birth to Adulthood. Cornell University Press, 1992;

(3) Bonanno, George A. The Other Side of Sadness: What the New Science of Bereavement Tells Us About Life After Loss. Basic Books, 2009;

(4) Cornum, Rhonda, Matthews, Michael D., and Seligman, Martin E.P. “Comprehensive Soldier Fitness: Building Resilience in a Challenging Institutional Context,” American Psychologist, 66(1): 4–9 (2011);

(5) Meichenbaum, Donald. Stress Inoculation Training. Pergamon Press, 1985;

(6) Rotter, Julian B. “Generalized expectancies for internal versus external control of reinforcement,” Psychological Monographs, 80(1), 1966;

(7) Gross, James J., and John, Oliver P. “Individual differences in two emotion regulation processes: Implications for affect, relationships, and well-being,” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 85(2): 348–362 (2003);

(8) Figley, Charles R. Compassion Fatigue: Coping with Secondary Traumatic Stress Disorder in Those Who Treat the Traumatized. Routledge, 1995.